But she’s no theologian, or shepherd, or mother, and frankly, sometimes she just doesn’t get it. She’s smart, she’s well-read, she’s poetic and gracious and observant and interesting and a skilled writer. Norris is highly critical of the anti-liturgical, anti-intellectual, and anti-art culture produced by much of America protestantism (often rightly so in my opinion), but the problem is that she isn’t in a position to appreciate or even recognize the motivation behind the theology and ecclessiology that has driven the reformation in the past and the evangelicism of our current time. I dare say that if she had been truly stuck there, like all the other residents, she might have written a different book. Still, she isn’t constricted by vows and frequently has to leave for a weekend to jet off to Hawaii or Manhattan to take care of business. She might have learned a lot in her 9 months in the monastery and it’s often delightful when she shares what she has discovered. The defense is welcomed, but the other not so much. I don’t think it’s a stretch to say that her memoirs frequently glamorize and defend the monastic life. She isn’t even tied down by her husband who is distant and independent, often living in foreign countries for a year or more at a time without her. She has no children to care for, not even grown children or grandchildren to visit.

She’s relatively wealthy and financially well-off without the need to work on a day-to-day basis and hold down a job to pay the bills. It makes complete sense that Norris finds living casually in a cloister to be a sublime and positive experience.

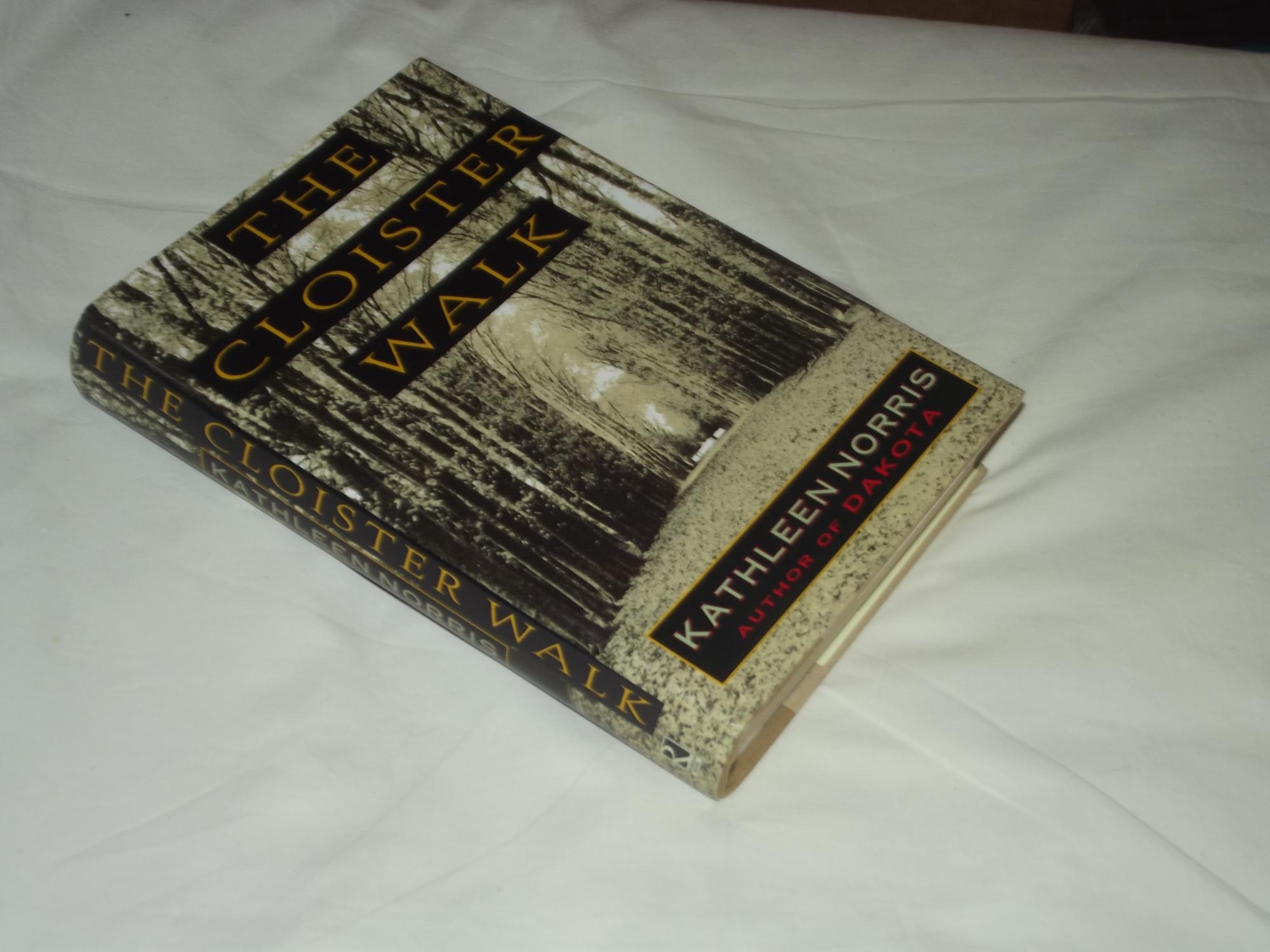

The Cloister Walk takes place a few years later and recounts the year she spent in a Benedictine monastery. Her first memoir, Dakota (which I picked up on a whim at a used book store a few years ago) was surprisingly great. It’s a bit hard to write this somewhat negative review since I actually really enjoyed the book, especially the first half.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)